Words matter.

We hear it all the time, but the significance of the statement extends well beyond the popular interpretation.

Words matter, not only in the moment they are spoken but as the collective inventory of language they come to represent, one that informs how we experience ourselves and each other. Like bricks in a foundation, the words we hear, think, and say together form a structure in which we live, and a springboard for how we show up in interactions and relationships.

Words we hear

The words we hear early in life lead us to develop our sense of self, to form opinions and mindset, like guides that help us navigate the world around us. If we repeatedly hear words like you can, the structure evolves with strength and empowerment, filled with positive and purposeful thought patterns. Conversely, if we routinely hear words like you can’t, shouldn’t, or don’t dare, the structure could be left wanting, weak, one where curiosity and big ideas are stifled.

A demeaning comment from a family member decades ago that questioned your career choice is one example. Words that, when heard, may have dented your resolve, diluted your confidence. Or an off-handed jab by an old manager about your tendency to be “dramatic” that discouraged you from speaking truth in future confrontations. Or perhaps a college professor who described your writing skills as “flimsy,” words that echoed in your ear every time you considered submitting an article or essay.

The possibilities are as infinite and unique as human fingerprints. Hurtful or humiliating words are stored in the body and brain, like bits of information on a hard drive, and remain there until our stress response is triggered by a similar situation or interaction. To believe that such imprinting vanishes over time or can be summarily dismissed is not only naïve but can hold us back from reaching our potential, from feeling good in our skin.

Still, we try to ignore unpleasant memories, maybe assuming that to do otherwise is immature and petty. On the contrary, understanding the parts of our past that continue to affect us is a powerful form of self-care that can enlighten us in the present. It is not an invitation to dwell or fixate, nor is it intended to assign blame or pass the baton of responsibility. Rather, the exercise allows us to take agency, to empower ourselves by tapping into the forces that have influenced us, to make choices that serve us better rather than falling prey to habits that don’t.

In his book, Permission to Feel, Marc Brackett, PhD, puts it this way:

“Until we can recognize our own emotions, we can’t learn the skills necessary for regulating them. To recognize our emotions is to acknowledge that we’re all feeling beings and we’re experiencing emotions every instant of our lives.”

Words we think

This seminal foundation of words we hear forms the basis for a second layer of our language inventory—the words we think, or the inner dialogue we create in our minds. Human beings are meaning-makers, driven to explain everything that happens whether armed with the requisite facts or not. The expression on the face of the bank teller, the driver that cuts us off on the highway, the co-worker who appears grumpy during the weekly meeting—these are but a few examples of situations that trigger our urge to fill in the blanks. And, once we spin our stories, we look for reasons to believe them—one of the myriad cognitive biases that we succumb to on a regular basis.

But the fact that we believe our own thoughts can be problematic. From a practical standpoint, it can lead to faulty assumptions and predictions that, in turn, can encourage us to choose thoughts and behave in ways that fuel misunderstanding, harm relationships, even foster resentment. All because we are operating under a cognitive shroud of our own making. From a neuroscientific standpoint, convincing ourselves that potentially fictional narratives are true strengthens corresponding neural pathways so that we become prone to similar thought patterns next time. Unlike feelings, which we cannot control, our thoughts are choices, and those choices can cause our brains to fire in ways that may not serve us well.

But here’s the good news: we can make different choices, adopt thoughts that serve us better, thereby strengthening different neural pathways.

While it has long been understood and accepted that the brain’s wiring changes when we learn a new skill or language, research has shown that shifts also occur when we merely think about engaging in a new activity. Scientists refer to this capacity as neuroplasticity. What it implies is that by changing our thoughts, we can change our brain’s wiring.

Imagine the possibilities.

But knowing you have the power is one thing. Believing it and experiencing the change that can occur requires commitment and resolve. Consider the words of the good witch Glinda in the film, “The Wizard of Oz,” when a homesick Dorothy was shocked to hear her say, “You have always had the power to go back to Kansas.” But when the Scarecrow asked why she hadn’t shared this news sooner, Glinda replied, “Because she wouldn’t have believed me. She had to learn it for herself.”

Like learning to ride a bicycle. As young children, we are assured that the process will end in success. Still, it seems impossible when we first hoist ourselves on the seat, steady our feet on the pedals, then wobble our way down the road supported by training wheels. The more we do it, the less often the training wheels touch the road. A process we don’t notice since they’re at the back of the bike and our attention is focused forward. When they stop touching down all together, we’re told it’s time to remove them, but we don’t quite believe it. That is, until we experience the first untethered ride, one that feels nothing short of miraculous.

Words we say

Finally, the words we hear and think fuel the words we say.

This isn’t a leap: if our early imprinting (words we hear) and inner dialogue (words we think) are laced with negativity, there’s a good chance we’ll mimic those dynamics in how we show up with others. Which makes understanding the potpourri of language running in the background of our brains critically important.

But like our brain’s wiring, the word banks we draw from are not intractable. With practice, we can renovate them, like a tired bathroom or kitchen. The upside is real: by adopting different language habits that align with the thoughts we would prefer to think, we can positively influence how we present ourselves to the world.

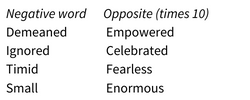

But how? One strategy that works well is a Word Bath exercise: think of a word that describes an uncomfortable or negative feeling, then think of another word that describes the opposite feeling, times 10. Write the positive word on a piece of paper or in a device.

Here are a few examples:

Repeat the task until you have generated a list of about 15 positive words. Then, for a week or two, recite the list out loud to yourself a couple of times a day, slowly and deliberately so you can process and internalize them. The process is made more effective by speaking the words, since you will be lighting up both hemispheres of the brain: the left hemisphere (the language center) and the right hemisphere because of the feelings associated with them. This exercise represents a powerful tool in reframing a view of self that has been fueled by negative language.

What it all means

Each of us has the power to effect real and positive change in the way we experience ourselves and others by understanding the framework of language that has influenced us over our lifetimes. While it begins with words, it ultimately rests with our choices and willingness to lean into reflection, discovery, and curiosity. To understand our own wiring and, in so doing, to shine a light on what has long been hidden so we can create experiences by choice instead of by default.

It seems that when it comes to words, the final one rests with us.

This article was originally featured by Elephant Journal on May 23, 2022.

Recent Comments